A village of tents has arisen on the New Haven Green. Its inhabitants each has a slightly different reason for being there. They all share one thing in common, though: dissatisfaction with growing social disparity.

This is Occupy New Haven, a local offshoot of the global Occupy Wall Street protest movement that began Sept. 17 in Zuccotti Park, New York City. It has its own local flavor to it.

It's Personal

“Moose” declines to give his real name. He, like several others in his community, is wary of the media.

He wears a sign draped around his neck that reads, “Department of Hornland Security. When asked why he wears it, he pulls out a makeshift horn and blows into it like a megaphone.

Moose says he moved to New Haven from New Hampshire nine years ago. He graduated from UNH in 2006, but is currently unemployed. So is his fiance, who attained a master's degree in psychology. They're saddled in over a hundred thousand dollars in student loans.

“I have a hard time identifying the difference between that and indentured servitude,” he says.

Not too long ago, he points out, finishing an undergraduate degree was considered a major accomplishment. “Now a bachelors degree is the equivalent of a high school diploma,” he says.

Moose and his community plan to occupy downtown New Haven indefinitely. To do that, they have had to make a concerted effort to prepare and sustain themselves. They've developed more than ten committees to handle various tasks, from legal issues to safety to music.

The New Haven group has benefited from its later start compared to the first Occupy Wall Street encampment, says Moose. They have a permit from the city to be there. They began planning their supply needs before they moved to the green. They have an amicable relationship with the police.

They also have a much more expansive space. Zuccotti Park is a mere 33,000 square feet, or .076 of an acre. The New Haven Green is 16 acres. The camp only covers an out-of-the-way corner of the green. The area, surrounded by old New England-style churches and apartments, is idyllic for an occupation.

|

| A sign decries the differing rules that govern student loan debts and bailouts for large businesses. |

A Community Vision

Hundreds of people have shown up at some of Occupy New Haven's rallies. Some come and go freely throughout the day. Only a relative few stay overnight in several dozen tents strewn across the grass.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, the 99 percent are not protesting; they're searching out supplies, having individual conversations, eating and sleeping. On a Friday afternoon, a meeting of 25 or so convenes near the Information tent. They sit in a circle on the ground or in lawn chairs.

One wonders if there should be more regular meetings. A debate ensues over whether to move some meetings to earlier times or keep them later to allow for people getting out of work to come. Someone asks if smaller meetings could take place throughout the day.

A woman at the outskirts of the circle notices that a car in the street is being towed. She stands up and calls, “Mic check!”

“Mic check!” the others around her call out in unison, using the group amplification tactic called the “human megaphone.”

“Someone’s car is getting towed,” she says. The group repeats the sentence. Everyone looks out to the street, but no one moves to claim the car. The meeting continues.

|

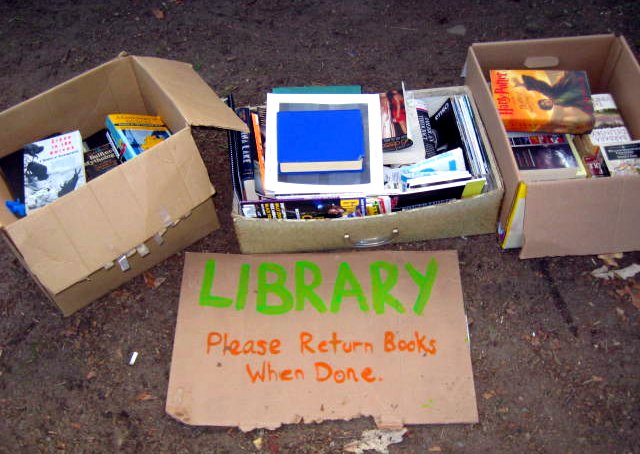

| The occupiers have a number of makeshift public institutions, such as this “library.” |

Afterward, Amanda Taylor returns to the Comfort tent to sort clothes and blankets. As a member of the Comfort Committee, it's her job to manage the inventory.

She takes her task seriously. The days are getting colder, and there are incoming donations to sort and distribute.

Taylor grew up in North Stonington, and this is the first time she's been to New Haven. She has felt the sting of economic inequality. Her family had little money when she was growing up. She didn't go to college because she couldn't afford it.

In New Haven, though, she learned just how wide the economic gap can get.

“I'd never seen a homeless person before,” she says. “It's really sad. People aren't homeless in North Stonington.”

Some of the clothing donated to the Occupy New Haven group, she says, now go to the local homeless community, many of whom spend most of their time at the New Haven Green.

Taylor is glad to be helping others in a tangible way, even as she struggles with her fellow protesters to spur action from the most powerful in society.

|

| Comfort committee member Amanda Taylor takes stock of some of the demonstrators’ supplies. |

Organizational Networking

Win Heimer is trying to coordinate Occupy New Haven with its correlate in Connecticut's capital, Occupy Hartford. He is not a member of either, but he wants to support both with supplies and services.

Heimer is a union representative with the Alliance for Retired Americans, and part of the Greater Hartford Central Labor Council.

Several unions across the country have joined in demonstrations. The worldwide phenomenon that began near Wall Street is combating economic injustices that Heimer says he's been fighting against for a long time.

Heimer and his associates at a local union have arranged buses between New York, New Haven and Hartford. He says he is hoping to find a biodiesel generator for the encampment on the green.

Heimer is careful not to try to push the groups in a particular direction, however. Everyone prefaces their statements by saying they do not speak for the group, including him.

“This movement has just started. We have to see where it goes,” he says, adding, “hopefully it will bring changes that benefit our children and grandchildren.”

|

| A message of peace decorates the medical tent. |

Martina Crouch, a New Haven resident, is also hoping that the movement brings changes. She says she joined because she found people who thought like she did there. Then she realized that the protests could become a launching pad for something greater – a community conversation.

A number of the Occupy New Haven demonstrators note that they view their role in movement as an opportunity for local change. Crouch agrees with that sentiment. In this sense, one of the main themes of the their protest sounds like twenty-first century version of a distinctly New England tradition: the town hall meeting.

She says that the media cannot possibly portray the culture of the occupiers as well as experiencing it firsthand.

“Whatever preconceptions you may have,” she says, “you should come down and see what it really is.”

Occupy New Haven has become a microcosm, a society within a society. For Crouch and her tent community, that in itself is a great success.

“These protests brought people together,” she says.

|

Signs are carefully arranged on the ground in one corner of the encampment when they’re not being used.

|